A wine of subtle prestige: The Enduring Allure of Tokaji

Tokaji may look gentle and golden, but it’s breaking rules, reclaiming heritage, and redefining what wine lovers should pay attention to.

If you’re still thinking of sweet wine as the predictable epilogue to a meal, or as something a caring friend or elderly relative brought out at Christmas, but remained unopened since 1998, then Tokaji hasn’t properly crossed your path. And that’s a shame, because Hungary’s golden elixir isn’t just a sweet wine; it’s a masterclass in balance, structure, and longevity. It’s a cultural artefact in a bottle, and at its best, it’s nothing short of a revelation in how we understand and appreciate wine itself.

Now, we’re not going to drown you in florid tasting notes or bludgeon you with “puttonyos” statistics, though we’ll get to those in due course. Instead, let’s take our time. Tokaji doesn’t hurry, and nor should we. This isn’t about acquiring a casual trivia fact to drop at a dinner party; it’s about falling in with a wine that rewrites what you thought you knew about sweetness, age, and elegance.

We’re heading to the misty hills of northeastern Hungary, to volcanic soils and fog-shrouded mornings, to vineyards with vines that have withstood empires rising and crumbling. This is where Tokaji is born. Or more specifically, where it’s quietly perfected.

A region that knew its worth before you were born (and before Bordeaux did, too)

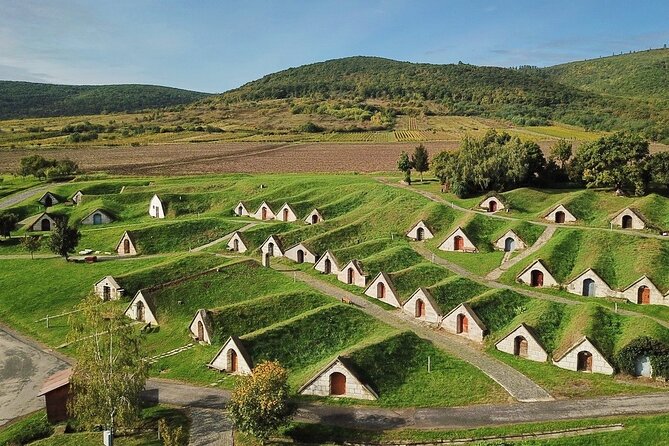

The Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region – literally “Tokaj foothills” – sits in the far northeast of Hungary, not far from the Slovakian border. Here, the Bodrog and Tisza rivers converge, contributing to a microclimate that practically begs for noble rot. Those morning fogs, followed by dry afternoons, are exactly what Botrytis cinerea needs to work its magic. And it does. Consistently.

This is no obscure upstart region. Tokaj-Hegyalja is officially the oldest classified wine region in the world, dating back to 1737, a good century before France’s big names got around to formalising anything. The Austro-Hungarian nobility knew what they had on their hands, and so did the popes, emperors, and literati of Europe who imported it in extravagant quantities. Voltaire adored it. Catherine the Great reportedly ordered Russian soldiers to guard Tokaji cellars. If your favourite wine bar or high-end restaurant isn’t offering it, you might want to reconsider your choices.

Grapes with a genetic predisposition for greatness

If you’re the kind who likes your grapes to sound like forgotten instruments or mountain herbs, you’ll love the Tokaji cast. The leading actor is Furmint, a grape with acidity to rival Riesling and an almost architectural sense of structure. It’s capable of electrifying dryness, but when botrytised, it carries sweetness with staggering finesse.

Next is Hárslevelű, often described as more aromatic and delicate, contributing perfume and a kind of golden softness to the blend. Then you’ve got Sárgamuskotály (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), Zéta, Kövérszőlő, and Kabar in supporting roles – adding nuance, tension, and, occasionally, floral mischief.

But Tokaji isn’t just about varietals. It is about what happens when they’re hit by noble rot. The result is the famous aszú berries: shrivelled, raisin-like, and loaded with concentrated sugar and acidity. These are handpicked, often over multiple passes through the vineyard, and then macerated into a base wine or “must”. It’s a painstaking process, more akin to alchemy than agriculture.

Puttonyos, sweetness, and a lesson in balance

Historically, Tokaji Aszú wines were measured by puttonyos, as a reference to the number of baskets (puttony) of aszú berries added to a “Gönci barrel” of base wine. Gönci barrel is a Hungarian oak barrel, historically used for Tokaji Aszú production. It’s named after the village of Gönc, where these barrels were traditionally made. More puttonyos meant more sweetness, with the scale running from 3 to 6. But don’t get too attached to those numbers as they’re largely symbolic now.

Today, the law requires all Aszú wines to have at least 120 grams of residual sugar per litre, which used to correspond to the old 5 puttonyos level. So most modern Aszú is made to this rich but still remarkably fresh style, and if you see a 6 puttonyos, you’re likely looking at something with 150+ grams/litre.

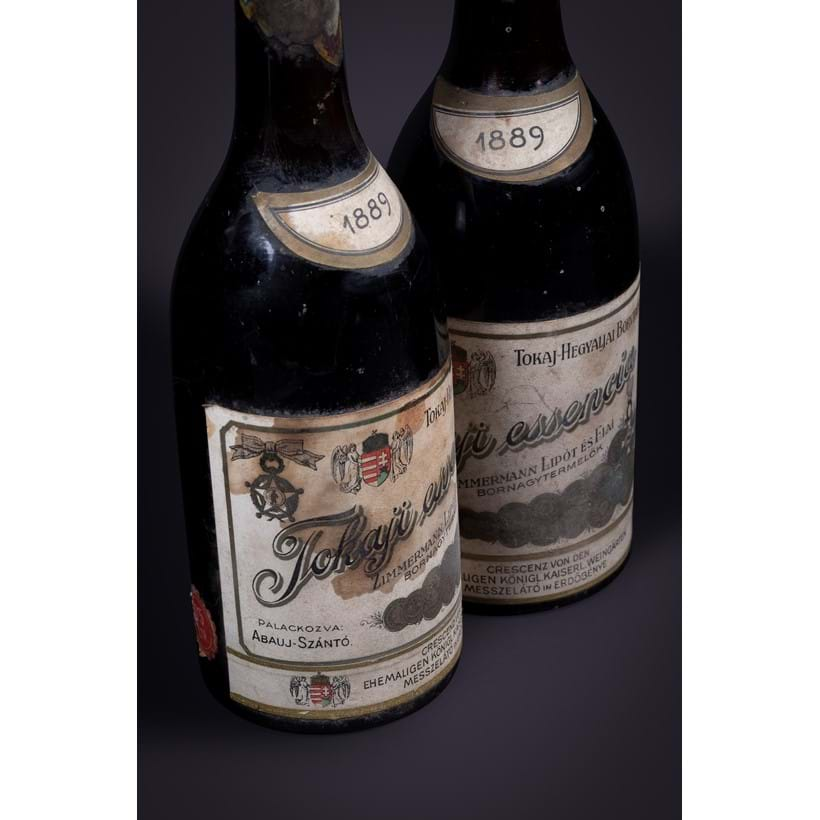

And then there’s Essencia. The stuff of legend. Pure free-run juice from aszú berries, no base wine involved. It ferments so slowly, often taking years to reach a whisper of alcohol (around 3 to 6%), because the sugar levels are absurd. Sometimes 700 grams per litre or more. It’s thick, syrupy, eternal. Think honey laced with lightning. Essencia is sold in impossibly small bottles, often with a glass spoon. And yes, it’s eye-wateringly expensive. But it’s one of the only wines in the world that feels entirely justified in calling itself liquid gold.

Sweetness, with layers and lineage

So let’s get one thing straight. Tokaji Aszú isn’t just sweet. It’s structured. The acid levels in Furmint are what allow these wines to age for decades, even centuries. A well-made Aszú from a strong vintage will carry its sugar on a blade of brightness.

In the glass, you’ll often find a cascade of dried apricot, marmalade, quince, orange peel, saffron, wildflower honey, even hints of tobacco or black tea. The finish is almost inexhaustible. There’s a subtle oxidation at play, not unlike the nutty edge in old sherry, but rounder, more honeyed.

And that acidity? That’s the revelation. It keeps Tokaji honest. Where lesser sweet wines might descend into syrupy sentimentality, Tokaji stays sharp, alert, alive. It’s dessert wine for people who secretly hate dessert wine.

Producers to seek, covet, and quietly hoard

In Tokaji, names matter. And while the region has seen a revival over the past 30 years, the real quality lives with a few key producers who treat this wine as both heritage and art form.

Szepsy is the talisman. István Szepsy is descended from the family credited with formalising the Aszú process, and he continues to turn out some of the most thrilling wines in the region. His bottlings are rarely cheap, but they set the benchmark.

Royal Tokaji, co-founded by British wine writer Hugh Johnson in 1990, helped bring international attention back to the region. Their wines are widely distributed and consistently excellent, making them a smart entry point.

Disznókő offers sculpted, elegant Aszú with a house style that’s refined and textural. Their dry Furmints are also worth chasing down.

Then there’s Oremus, owned by Spanish powerhouse Vega Sicilia, which brings a certain gravitas and polish to the table. Their range includes both traditional and innovative expressions, always with that unmistakable Tokaji verve.

You’ll also hear whispers about Demeter Zoltán, Barta, and Tokaj Nobilis – smaller producers who punch well above their scale. Their wines are often harder to find, but immensely rewarding.

The dry side: Furmint unleashed

Don’t be seduced solely by the syrupy side of Tokaji. Dry Furmint is one of the region’s best-kept secrets, and a compelling alternative to Chablis or dry Riesling. The same acidity that powers Aszú becomes a precision tool in dry form, giving these wines a mineral, almost saline character, with orchard fruit, spice, and a distinctly volcanic edge.

Served cool, they’re sensational with food, particularly Hungarian fare (duck with cherry sauce, goulash, foie gras) but equally at home with smoked fish, Alpine cheeses, or pork belly. Furmint doesn’t try to charm; it earns its way into your good books.

Tokaji in context: why now?

Here’s the quiet truth: Tokaji is still undervalued. In an era when Burgundy prices have entered the absurd and Champagne is increasingly treated like a commodity, Tokaji Aszú offers staggering complexity, longevity, and cultural depth for a fraction of the cost.

The fact that so few collectors talk about it means there’s still time to build a serious cellar without selling your furniture. That won’t last forever. The quality has never been higher, the vintages are increasingly reliable (blame or thank climate change), and international palates are finally opening up to the idea that sweet doesn’t mean simple.

How to drink it: slowly, seriously, and socially

A good Aszú doesn’t need food, but it adores it. Try it with foie gras if you want to play the classic card. Or with blue cheese, roast figs, or even sushi if you’re feeling inventive. Tokaji can handle spice, umami, and salt in ways that baffle other wines.

Serve it slightly chilled, around 10–12°C, and always in a proper wine glass. The dessert wine flute is an insult. Decant older vintages, or younger ones that feel closed. And don’t rush. A single glass can unfold over an hour.

A Toast to Something Enduring

Tokaji isn’t trying to be fashionable. It doesn’t trade on trends or chase fleeting approval. It simply is what it has always been: complex, noble, patient, and entirely in a class of its own.

To drink Tokaji isn’t just to enjoy a wine. It’s to step into a centuries-old conversation between soil, grape, and human effort. It’s a reminder that sweetness, when balanced and brave, can carry more power than the sharpest dry wine.

So next time you see that familiar squat bottle, clear glass, golden hues – don’t dismiss it as a sticky curiosity. Raise a glass, taste it slowly, and join the ranks of those who know. There’s no need to rush. Tokaji reveals its legacy in layers – subtle, enduring, unforgettable. And for those who learn to listen, it speaks softly, but it speaks of centuries.

Wineries Worth Visiting

Embarking on a journey through Tokaj-Hegyalja offers the opportunity to explore a variety of wineries, each with its own story and expression of the region’s signature grapes, Furmint, Hárslevelű, and Sárgamuskotály.

- Royal Tokaji: Co-founded by wine writer Hugh Johnson, this estate has been instrumental in reviving Tokaji’s international reputation. Their wines balance tradition with modern elegance.

- Oremus: Owned by Spain’s Vega Sicilia, Oremus combines meticulous craftsmanship with a deep respect for Tokaj’s heritage, producing wines that are both expressive and refined.

- Szepsy: Often considered the patriarch of modern Tokaji winemaking, István Szepsy’s commitment to quality and terroir expression has set a benchmark for the region.

- Tokaj-Hétszőlő: With vineyards dating back to the 16th century, this estate offers a blend of historical significance and organic viticulture practices.

- TR Wines: A boutique winery in Tállya focusing on organic farming and minimal intervention, showcasing the purity of Tokaj’s terroir.

All materials are reproduced in good faith and remain the copyright of their respective owners. ©Luxfanzine, 2025